By Jeff Foust

The United States is returning to the Moon, and this time it intends to stay there.

Ever since President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration program (VSE) in January 2004, the focus has been on NASA’s plans to return to the Moon. Over the last three years, the space agency has worked on plans to develop the spacecraft and launch vehicles and other systems needed to mount the first human mission to the Moon since Apollo 17, in 1972. In the backs of everyone’s minds, though, was a nagging question: Then what?

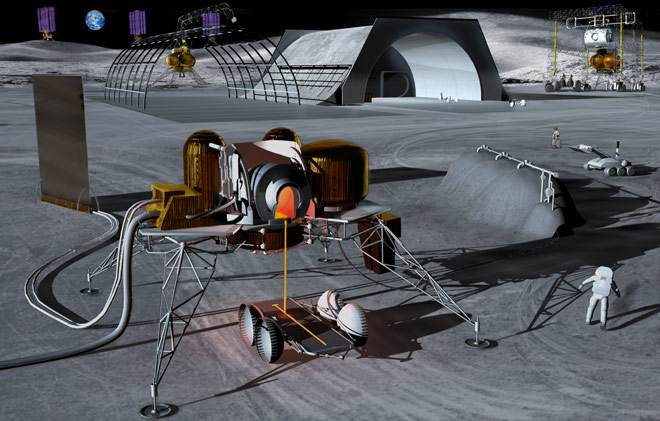

In December NASA provided at least a partial answer to that question when it unveiled the Global Exploration Strategy and Lunar Architecture Study, two efforts to explain what NASA will do on the Moon upon its return and how it will do it. The centerpiece of those plans is something that is both straight out of science fiction and long hoped for by space advocates: a base on the Moon.

WHY A MOON BASE?

Since the VSE’s introduction three years ago, many had assumed that some sort of lunar base would be part of NASA’s plans. In his speech at NASA headquarters to unveil the VSE, President Bush spoke about “extended human missions” to the Moon “with the goal of living and working there for increasingly extended periods.” NASA documents since then that detailed the agency’s long-term plans often referred to a “lunar outpost buildup” shortly after humans returned to the Moon.

However, NASA officials said that the current plans for the base emerged from efforts to explain why humans should go back to the Moon and what they can do there. “Our approach is one in which the architecture is definitely driven by the strategy that has been developed, the Global Exploration Strategy,” said NASA Deputy Administrator Shona Dale. “The Global Exploration Strategy developed themes and objectives, and these objectives have led directly into the lunar architecture.”

The Global Exploration Strategy was a NASA-led effort started in April 2006 that involved over 1,000 people, including representatives from 14 national space agencies, to identify the types of activities that could be done on the Moon. During a series of meetings, participants identified 180 potential objectives for lunar exploration in 23 categories, ranging from astronomy and lunar geology to commercialization and testing of technologies, needed for future human missions beyond the Moon.

As a part of that effort, six themes for human lunar exploration emerged: human civilization, scientific knowledge, exploration preparation, global partnerships, economic expansion, and public engagement. These broad—if somewhat vague—themes are intended by NASA to encapsulate all the possible rationales for exploring the Moon.

With that wish list of potential objectives in hand, a separate NASA team evaluated which approach would work best to fulfill them: a series of short-duration missions similar to the Apollo program, or the establishment of a base of some kind. The Lunar Architecture Study concluded that a base is the better approach. “It enables global partnerships, allows for maturation of in situ resource utilization and results in a path that is much quicker in terms of future exploration,” said Dale. “Also, many science objectives can be accomplished in terms of pursuing an outpost.”

Scott Horowitz, a former astronaut who is now NASA’s associate administrator for exploration systems, said that the conclusion to develop a Moon base had wide support from both scientists and engineers, two groups not always known for getting along well with each other. “It is one of the few cases where I have seen the science community and the engineering community actually agree on anything,” he said.

HOW AND WHERE

With the questions of whether and why to build a Moon base out of the way, NASA is now turning its attention to where and how to build such a base. While those plans are still in their earliest stages—understandably so, given that the base won’t be constructed until at least the early 2020s—NASA has started to make some early decisions about the design of the outpost.

One of those decisions is to locate the base somewhere near the north or south poles of the Moon. At the December 4, 2006, announcement of NASA’s lunar base plans, officials even identified a specific Location: along the rim of the crater Shackleton, near the south pole, though they stressed that this location could change depending on the data returned by upcoming missions to the Moon, such as the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2008.

The lunar poles have long been considered a prime location for a base because of the Moon’s low obliquity, or axial tilt. That means the Sun hangs low on the horizon at the poles for most of the lunar day, helping avoid the baking heat of the two-week lunar day and freezing cold of the equally long lunar night found elsewhere on the surface. In addition, mountains near the poles could receive near continuous sunlight while crater interiors can remain in permanent shadow, serving as “cold traps” for ice and other volatiles.

Doug Cooke, NASA deputy associate administrator for exploration systems, said that the proposed site on the rim of Shackleton receives sunlight 75 to 80 percent of the time, although there may be other areas there or at other craters that receive sunlight continuously. “We don’t really understand that entirely yet because we don’t have a full year of coverage from orbital assets, which we intend to get with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter,” he said.

Near continuous sunlight has a very practical advantage for a lunar base: It allows the use of solar power. A base outside the polar regions would likely require nuclear power to generate heat and power through the long lunar night, something that would add considerable cost, as well as potential political and environmental complications, to the project. “We can definitely move later into nuclear power, but that will be much easier in terms of operations in the beginning,” said Dale.

What exactly the base will look like and how big it will be have yet to be determined. NASA officials said that it will in part depend on what roles potential international partners or even the private sector want to play in terms of supplying modules or cargo for the facility. NASA plans to gradually build up the base’s infrastructure over several years with a series of short-duration human missions so that by approximately 2024 the base can support permanent occupation by a series of crews that rotate every six months, similar to how the International Space Station is run today. Additional modules and equipment could be added later, such as a pressurized rover to enable long-range expeditions from the base.

The key to building up the base is developing a lunar lander big enough to carry key equipment to the base while versatile enough to perform many different missions. “The nickname I use for the lander is ‘pickup truck,'” said Horowitz. “You can put whatever you want in the bed.”

“In looking at the Lander, it is important to maximize the landed mass,” said Cooke. “What you can put on the surface allows you to develop a capability much more quickly: The more you can land, the better it is.”

CHALLENGES AHEAD

While the Moon base plans help provide a focus for NASA’s overall exploration efforts, they also illustrate just how far off in the future those plans are. The lunar kinder considered so essential to developing the base exists as only a notional concept: A preliminary design review for the vehicle isn’t planned until between 2011 and 2013. Similarly far in the future are the Ares 5 heavy-lift launcher and the Earth Departure Stage needed for lunar missions.

Work is under way on the Orion spacecraft (formerly the Crew Exploration Vehicle) and its Ares 1 launcher, but budget problems could slow down their development. Congress adjourned in December without passing a NASA budget for the 2007 fiscal year, and the new Democratic leadership of Congress plans to replace the pending appropriations bills for NASA and other federal agencies with a yearlong stopgap funding bill. That would fund NASA at essentially the same level as 2006, denying it a small but critical budget increase.

The change in control of Congress may also lead to more scrutiny of NASA’s overall exploration plans. “Like our bases in Antarctica, a Moon base appears to offer the promise of a research facility that could advance our knowledge, prepare the nation for future exploration and promote international cooperation in science and technology,” Congressman Bart Gordon, new chairman of the House Science Committee, wrote in an editorial in the December 23, 2006, issue of the newspaper The Tennessean. “However, we will need more specifics from NASA and the President to fully evaluate the current Moon base proposal for its value, feasibility and, of course, affordability.”

Despite these near-term obstacles, NASA is optimistic about the long-term potential offered by a Moon base. “This is an evolving program. It is not about a single point in space and time,” said Horowitz. “We are after a generational program. What you are seeing here is the foundation, and the vehicles that we are designing are the vehicles that will be flown by the next generation of space explorers.”

Jeff Foust is a launch industry analyst with the Futron Corporation of Bethesda, Maryland, and publisher of The Space Review, a weekly online space publication, and of Spacetoday.net, a space news aggregator. He also operates the Space Politics weblog.