Spacesuits, Firefighters, and Helping Heroes

By Marianne J. Dyson

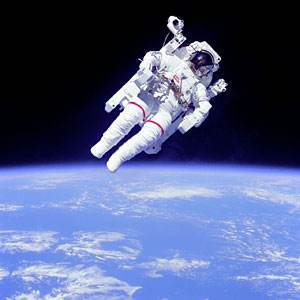

NASA has developed special suits to handle the harsh environment of space and also to deal with toxic and explosive propellants on the ground. As we all witnessed during the aftermath of the tragedy in New York and Washington, D.C., urban firefighters also have to deal with extreme temperatures and toxic compounds released during fires. Thus it makes sense that NASA technology is being adapted to help firefighters and military bio and chemical hazard cleanup crews.

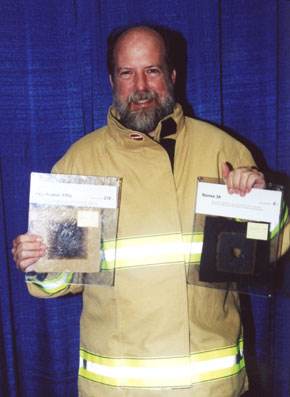

Work on this life-saving spin-off technology began in 1997, and the first fruits are expected to be ready for commercial sale this December. The program began when firefighter Gary Vincent, now the Assistant Chief of Planning and Research at the Houston Fire Department, brought a badly damaged helmet to NASA Johnson Space Center. He met with NASA engineer Tico Foley to explore ways to use NASA space suit technology to improve firefighter protection, endurance, and safety. “Many problems that they were facing were the same problems that we had already solved for the astronauts’ space suits,” Foley said.

According to Foley, there are three things that limit a firefighter’s time on the front line to about 20 minutes: 1) they run out of fresh air to breath, 2) the fire gets too hot even through protective clothing, and 3) the muscles create heat inside the clothes and get so hot even without a fire, the firefighter can die of heat stroke. Space suit technology is being used to address all three of these problems.

Foley joined a team of ten civil servants and several support contractors including Aerospace Design and Development, Oceaneering Space Systems, Johnson Engineering/SpaceHab, ILC Dover, Delta Temax, and Lockheed Martin, to work on transferring space technology to the private sector.

Critical Cooling

Heat stress kills more firefighters than smoke inhalation and even chemical poisoning. Yet conventional fire protective clothing covers the skin and interferes with perspiration. Trapped sweat and the physical stress of fire fighting combine to make the firefighters body heat and heart rate soar to dangerous levels. Heat stress forces most hazardous materials workers to stop work about every 15 minutes.

Dr. Hal Gier of Aerospace Design and Development, Inc. of Niwot, Colorado, working in cooperation with Kennedy Space Center and the U.S. Air Force, developed a solution. It’s called the Supercritical Air Mobility Pack (SCAMP) system and provides both body cooling and breathing from supercritical cooled (cryogenic) air. The cryogenic compressed air is in a vacuum bottle called a dewar. The cold air passes through a heat exchanger in the backpack where it is warmed by heat from the firefighter’s body to a temperature of about 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit that is comfortable to breathe. The firefighter wears an undergarment laced with tubes containing a flowing water and antifreeze mixture. The firefighter’s body heat warms the fluid in the liquid cooling garment. The liquid is then pumped to the heat exchanger where it is cooled by the cold air from the dewar.

“We don’t carry pure oxygen into a fire because of the fear of explosion,” Foley explained. “Instead, we carry compressed air — like in a SCUBA tank, only lighter weight than a SCUBA tank,” he said. A typical tank weighs about 30 pounds and lasts for a half hour.

Because the SCAMP cooling source is the same air that is being used for breathing, no additional systems are required to provide cooling. “This keeps the total weight of the box and garment to about 28 pounds and gives twice as much air as compressed air (bottles) of the same weight,” Dr. Gier explained.

The super-cooled (-320 degrees F at 750 psi) air is contained in a cryogenic dewar which replaces the standard self-contained breathing apparatus high pressure bottles in use now. “The air bottles they use now came from a similar effort using Apollo technology in the early 70’s,” Foley said.” Before the space program, they used big heavy steel tanks. The current firefighter air bottles, developed from NASA Apollo tanks, are composite material wrapped with Kevlar or fiberglass that gives them lighter weight with greater strength to carry much more air at high pressure.”

Because of higher fluid density and lower pressure in the dewar, the SCAMP backpack is both smaller and lighter than the old Apollo-derived compressed air bottles. The super-cooled air is in a single phase state, allowing SCAMP to be operated in any position, including upside down. The technology behind SCAMP came from the Shuttle program where super critical hydrogen and oxygen are used for life support and fuel cell systems.

A worker wearing a SCAMP unit can remain cool for a full hour of stressful labor, and two hours of moderate activity without having to resort to outside sources of cooling such as ice packs. Also, there is reduced logistics support because fewer air bottles are needed. “It is certain that there will be lives saved by the use of the SCAMP due to the increased time that emergency personnel can work without a refill,” Gier said.

How does the firefighter know when to get a refill? “A capacitor inside the tank measures the density of the air and a computer calculates how much air or time is left,” Foley explained. “The system has a beeper alarm and a liquid crystal display, which can be mounted in the mask to inform the firefighter when it’s time for a recharge.”

Keeping Heat and Toxic Fumes Out

The problem of keeping the firefighter safe from the heat of the fire is addressed by the use of a new fabric in the outer garment. Some existing suits are made from Nomex which was developed in the 1970’s, another spin-off from the Apollo program. Although a great improvement over firefighter suits prior to that time, “A blow torch could blow a hole through Nomex,” Foley explained. “Most current suits are made of a blend of PBI and Kevlar that can hold up to the heat of a blow torch and still withstand a force of 67 pounds before tearing.”

The NASA prototype suits are made of a fabric called Kevlar/PBO (Poly-phenylene benzobisoxazole) that is three times stronger than the PBI/Kevlar blend. “The same blow torch makes it turn dark, but doesn’t make a hole unless you press on it real hard,” Foley said. “This is important because the new fabric will give much more protection against the heat of the fire.”

Used in combination with the SCAMP, the worker would be protected from exposure to toxic fumes as well. “Because of the breathing apparatus, a firefighter would not have to worry about breathing dirty or contaminated air such as the asbestos and dust in the air after the New York attack,” Foley said. For this reason, the Air Force participated in the development of SCAMP. “They bought a couple (of the prototypes) and are evaluating them for protection when dealing with biohazards,” Foley said.

In fact, SCAMP’s first commercial use will be in fighting bio and chemical hazards. “The certification for use in hazard material suits is a precursor for use in a fire suit,” Foley explained. “Once it is certified by NIOSH (National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health), the suit can be used in hazardous material environments. The suit goes through another round of certification before it can be used in high heat environments.”

The High Cost of Saving Lives

SCAMP will be available to fire departments and the military in the very near future. SCAMP inventor Hal Gier’s son, Terry Gier, is Vice President of Administration for their company. He said that SCAMP was sent to NIOSH for certification the week after the attacks on New York and Washington, DC. “I should have the results back by the end of November,” he reported. “Once it is certified, then we can start selling the bottle and pack and water-cooled garment–it’s a complete system.”

The SCAMP system will initially cost $8,000. “Our goal is to bring the cost of our suit to about $6,000 once they are being made in quantity,” Gier said. A standard self-contained breathing apparatus bottle, which lasts about half an hour and does not offer any cooling, costs $2,000- $2,500.

But SCAMP will pay for itself by at least doubling the time on the job and also reducing recovery after fighting a fire. The younger Gier said, “In New York, after a few hours, they had brought in all the off-duty firefighters. By using SCAMP, instead of having to take a day off after fighting a fire to recover from exhaustion, they can be back on the job the same day. And, instead of having to bring in another shift of firefighters, they can use the existing shift longer.”

There are also long-term benefits to the use of SCAMP. Gier notes that many firefighters die young of heart attacks. The extreme stress of the job is certainly a contributing factor to these deaths. He cited an example of a firefighter called to clean up a chlorine spill at one of the big pools in Orlando, Florida during the summer. “The big heavy suits worn now for hazardous material cleanup are air tight, “ he said. “You start sweating as soon as you put it on.” The worker in Orlando was in the suit for less than a half hour. “They poured a bucket of water out of his suit when he took it off,” Gier said. “He ended up in the hospital from heat stress and dehydration.”

Gier feels that regular use of active cooling and longer-duration tanks will reduce both the physical and emotional stress of firefighting. After all, there is nothing more heartbreaking than not being able to rescue someone because the firefighter couldn’t get to them in time. “We’re reducing the stress they’re under,” Gier said. “We feel there’s a percentage of people that we’re going to save their lives who will never know it.” And those firefighters in turn, will be able to save more victims from fires and exposure to toxic environments.

Exploration is Key to the Future

Veteran astronaut John Young told a crowd at the ISDC last May that the kinds of technologies we need to survive in space are the same ones we need to deal with disasters on Earth: radiation protection, independent energy sources, efficient transportation systems, and recycling our air and water. He used the fallout from an asteroid impact or a super volcano as threat examples. “From what I know about impacts, sooner or later, we’re going to get taken out,” Young said. “The problem is right now, we don’t know when that sooner or later is.” He advised that to be ready, we needed to increase our efforts at exploring space. “ I sincerely believe that making progress in the exploration of space is the key to our future in this world.”

After the attacks in New York and D.C., many people fear that a coordinated terrorist attack could cause a very serious environmental disaster. The use of space suit technology for firefighters is just one example of how space exploration is giving us the tools and the confidence to deal with any disaster that nature or terrorists put in our path to a peaceful future on Earth and in space.